Several older respondents were dealing with transitions to semi- or independent living. The happiest of these were two respondents who lived in purpose- built supported accommodation. Although security was a problem (one had been burgled, the other kept a baseball bat handy in case of intruders), these young people felt relatively at home. In contrast, none of the respondents who had left care felt at home. Often they reported a lack of money and practical help to decorate, furnish, heat, deal with repairs and utilities. Kayden (16, independent living), interviewed a week after moving into a tiny council flat, had found a broken table, broken blinds, and a door he could not open – which later revealed a broken hoover. His attempts to contact the council were hampered by the lack of credit on his phone.

I’ve not got minutes to phone. I’ve only got text and you cannae text council.

Reggie, who did not know where he would be living until the day of his move, found on arrival that a previous resident had left large debts to utility companies and then ran up his own. He had received a lot of advice prior to this move, but much less support once he had left and needed to deal with these debts and council tax and housing benefit forms. A foster carer emphasised angrily how she felt that successful foster placements could be undermined by young people being given information about transitioning to independent living on the basis of age, rather than any consideration of a person’s emotional or practical ability to live alone, or of the type of living arrangements they were used to.

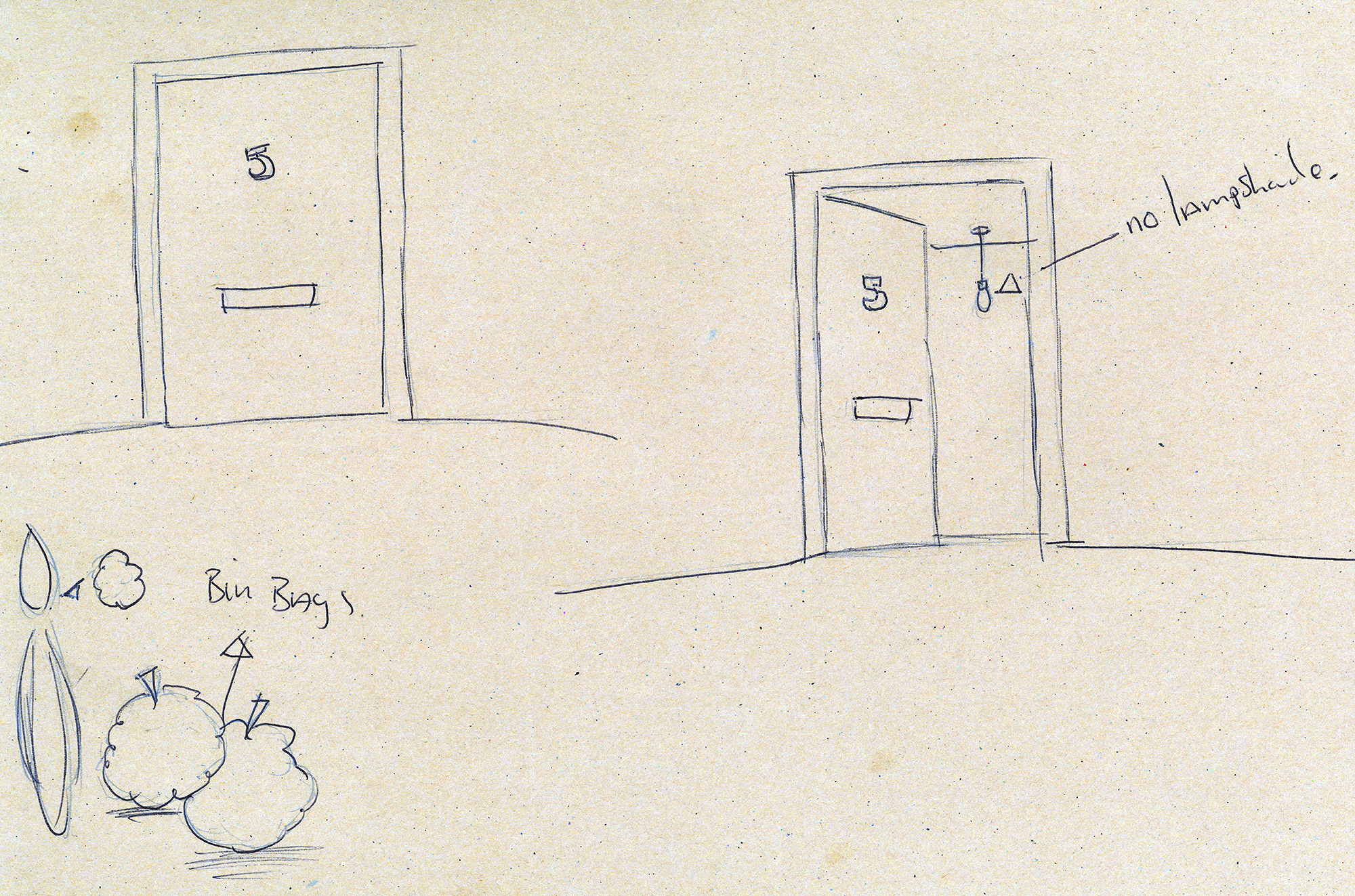

All four of the participants who were living independently hated where they lived, but felt obliged to stay due to housing law provisions on intentional homelessness. One respondent suffered panic attacks when alone in her flat, another was on medication for anxiety. After previous positive experiences of living in busy residential units, Dylan (18, independent living) and David both hated the silence of living on their own and spent most of their time at friends. Dylan tried to eradicate the silence with loud music and pet animals. David described a feeling of desolation – symbolised in his drawing by the lack of a lampshade after arriving at his bedsit with his belongings in plastic bags. After two years, he found he was still unable to decorate the flat:

I think it’s the isolation, I think it’s being by myself but I hate the place. I hate it. ..I didn’t decorate it but I know it won’t help [laughs].. I just don’t feel good there.

Another participant told us

I took a wee freak out/ black out sort of fit thing and chucked my bed out, so I’ve only got a mattress now [laugh]!.. I just hated everything in the house.

As a result of ‘the local connection’ test employed by local authorities, respondents were sometimes obliged to live in towns, or in Nedís case (17, part time foster care) on an island, where they did not feel they belonged. The location of flats could also be alienating; participants spoke of violence in surrounding streets or of keeping weapons hidden by the door for protection, while another disliked looking out on a landmark where young people who were in care had committed suicide.