Our research indicated that belonging is very complex. The spaces the participants felt they belonged included places and people not conventionally associated with ideas of ëhomeí or ëfamilyí. Personal items were of huge significance. Many participants worked hard to maintain connections across different spaces, but their access to important places was often fragile, dependent on strained relationships. Losing access to such spaces often affected their emotional wellbeing.

Spaces and belonging

Ideas of ‘home’ are often related to one living space associated with a ‘nuclear’ family. Several participants described such arrangements. They spoke of strong relationships with their carers and with pets, access to comfortable, private bedrooms, and feeling at ease in shared rooms and with the environment around their homes.

- Maylak (12, kinship care) identified how ‘happy’ he felt ‘just going into my house’

- Tiger (10, foster care) identified his comfortable bed, his bedroom, ‘his’ seat in a communal room that heíd helped decorate and ‘his space in the garden as his favourite places.

Several others spoke at length about how they’d decorated their rooms.

Leah’s room (20, adopted) reflected her love of bright, sparkly colours and objects, while Steven’s (16, secure accommodation) posters of New York represented his dreams of future travel.

For Plankton (12, foster care), emotional security came from living in small, tightly knit, rural community where she had come to know the local people well. She identified her bedroom, her foster carers, and their house, not only as her favourite spaces and objects, but also as her dream place to live.

Some respondents in residential care felt that generally they belonged, but were ambivalent about some aspects of these units. Often shared spaces such as living rooms were associated with unwanted noise and conflict. Marissa (10, children’s unit) feared another resident and avoided his room:

You feel a bit cautious like a time bomb’s going to go off.

However, some residents associated workers’ offices with comfort and safety, while bedrooms were particularly important.

Marissa’s bed and bedroom were among her favourite -and safest- spaces ‘because I can go there any time and it’s just me, nobody else.. and its got all my books and my bed and things in it. I just stay on the inside and there’s a sort of lock which you can turn easily’.

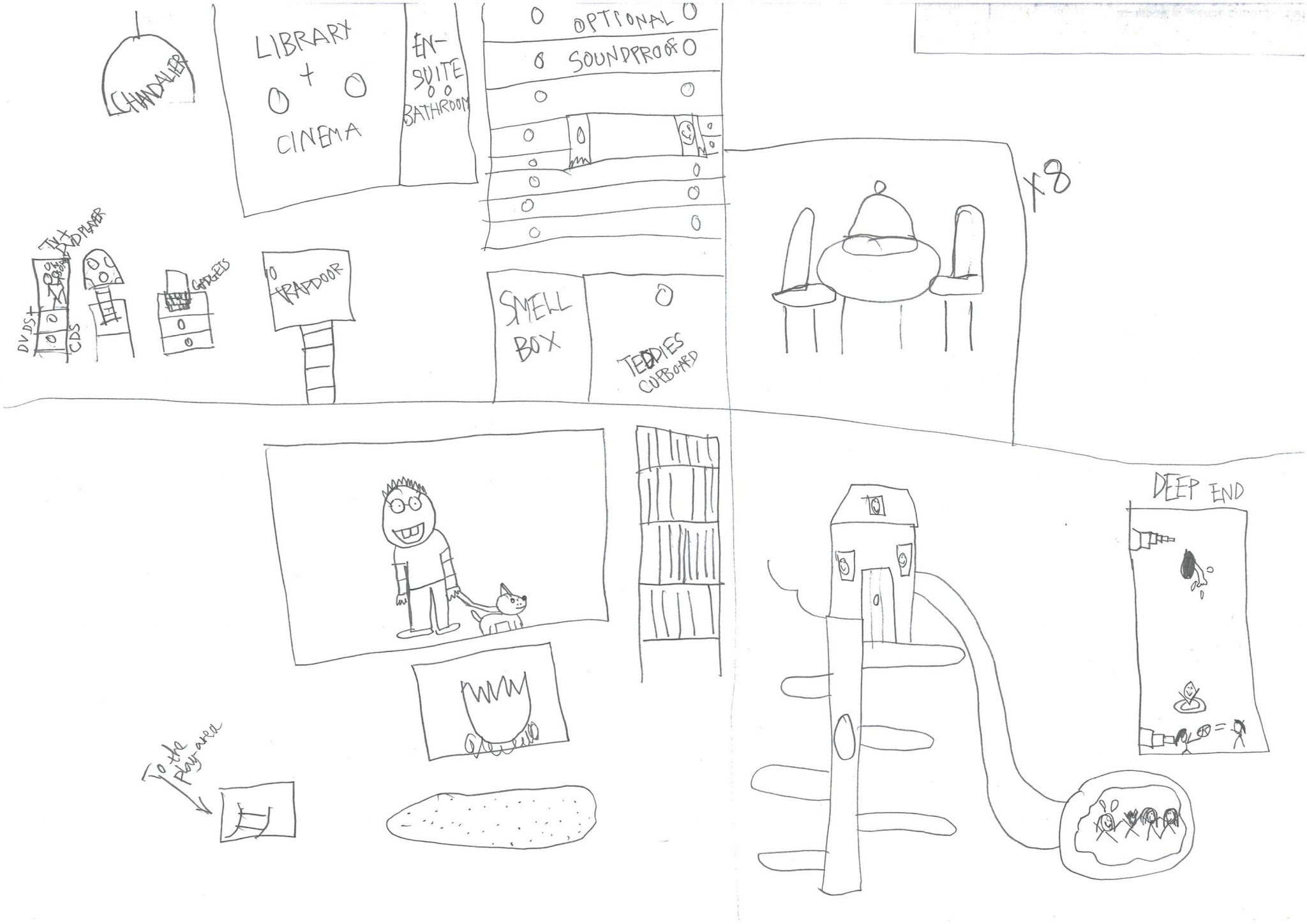

Security generally was very important. Like others, Marissa also highlighted the importance of small, private often ‘secret’ spaces, in which to be alone. For her, these included an alcove in her bedroom and a shed and tree in the garden. ‘My space is the shed outside..it’s really quiet and nobody thinks of looking for me there..sometimes I want to get away from it a bit’. The importance of physical comfort (beds, rugs, smell box), privacy (secret bed, soundproofing), personal items (books), in addition to a desire for safe, communal spaces (chairs and tables for the friends she couldn’t usually invite to tea in the unit) is obvious in Marissa’s imaginative drawing of her ‘ideal space’.

For secure unit residents with limited freedoms, such a sense of belonging was difficult (and potentially undesired). Thomas’ (14, secure unit) favourite places were his mum’s room, her house and garden and a nearby park where he met his friends, none of which he could access. He also ‘took all the decorations down’ in his room at the unit because he didn’t want ‘to make it homely or roomy..It’s not my home’.

Several older participants (some of whom had left care) hated where they officially lived, preferring to move between different points of networks of inside and outside spaces. In the islands, friends’ places provided a degree of privacy and shelter from the weather. In mainland Scotland, outside spaces were often important. In their networks of favourite places, Channel (17, foster care) included a beach and buses:

‘I don’t argue with anyone … all my feelings just go whoo… away from my head. I feel relaxed when I’m on a bus’

and Reggie (23, independent living) chose a park close to his former residential unit:

‘I still go there every week, walk through, just spend time there, it’s nice and peaceful..even when it’s busy’.

These networks often included places with family connections (Channel’s aunt’s house near the beach; Reggie’s mum’s place), but also friends’ flats, where they often slept.

These networks were fragile however and by the time of the second interview, Channel had lost access to her aunt’s and friend’s places, and Reggie to his mum’s, after arguments.